Clima

100% renewable electricity in the United Kingdom within 10 years

The electricity market in the United Kingdom has undergone a major transformation from having the majority of the generation derived from fossil fuels to a market with an equal share of fossil fuels and renewables thanks to the favourable wind conditions in the United Kingdom. The next step, which is a switch to generation entirely from renewables, is much closer than people realise. This has important implications for the next step which the market needs to manage successfully, the development of storage capacity to deal with the intermittency which is inherent to the nature of renewable generation. This looks like it will need to develop in the next 10 years and it is likely to happen, in my view, via a combination of political push to start with and price drag as the renewable capacity grows.

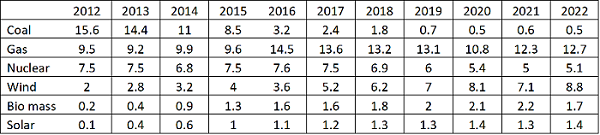

Some history to start with. The following table shows the electricity generation by major source over the past 11 years:

Source – National Grid: Live (iamkate.com)

To underline – coal has gone from being the major source of electricity to essentially nothing in 10 years. Let me repeat that because it is worth bearing in mind. Coal in 2012 was responsible for slightly over 40% of the electricity generated in the United Kingdom and is now under 2%. This is the poster child for showing what we can achieve when politics and price align. And this decrease in dispatchable supply and increase in intermittent, renewable sources to a third of supply happened without the grid ever coming under any stress. If the grid does fail, it is probably due to the grid operator not doing their job properly rather than the renewable sources not being able to be integrated into the grid.

So we currently have 28GW of installed wind capacity (14GW onshore, 14GW offshore) and 14GW of solar producing roughly a third of all UK electricity. This compares to 9GW of wind capacity and 2GW of solar in 2012. The government has set a target of 50GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030. This feels too aggressive as it means adding 4.5GW per annum when the highest rate previously has been 3.6GW in 2017 and 3.1GW in 2022 but an increase to 35/40GW seems possible looking at planned developments (Wind power in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia). While onshore capacity might increase by 4/6GW based on an increase of 0.6GW per annum. Solar capacity has been increasing slowly of late, from 12.5GW in 2017 to 14.4GW now so it might only increase another 3/4GW by 2030 (which would probably be better deployed in Spain or Italy anyway).

This looks like it should slightly more than double the wind generation of 80,162GWh in 2022 taking onshore capacity factor at 27.5% and offshore at 42%.

If I take the demand and generation figures over the course of the last year per week and double wind and solar while keeping nuclear production constant, I see a reduction in gas generation from an average of 12.5GW to 5.5GW and an average of 0.8GW that would need to be curtailed, roughly a week’s production. But add another 7GW of offshore wind capacity, maybe a further 3 years which means 10 years overall from now, and the amount of wind generation which needs to be curtailed (3.4GW per day) is slightly larger than the gas generation needed to otherwise balance periods when the wind is not blowing.

There may be years when demand is higher or the wind blows less, we will hopefully be electrifying everything so maybe we need more capacity but the broad picture is that, in around 10 years, the United Kingdom looks like it could use solely renewables to fulfill its electricity generation needs.

And it’s not just the United Kingdom. Spain looks like it could achieve this goal too. Wind accounted for 22% of electricity generated in 2022 while solar was 10% (Informe del Sistema Eléctrico: Informe resumen de energías renovables (sistemaelectrico-ree.es), page 7). The government wants to quadruple solar production and increase wind by 60%. Add in nuclear again at 20% of generation, and hydro at 6%, and Spain has 0 carbon electricity production in 2030.

What happens next is more interconnectors and storage.

Interconnectors work because they move electricity all around Europe. They already transport electricity back and forth between Norway, the United Kingdom, France, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Germany. The advantage of having, and enlarging, these interconnectors is that the European market will increasingly price down to the lowest cost generation source at that time. So wind turbines should be built more in the North while solar panels should be diverted to the south because the higher capacity factors make the returns better for everyone. The average solar capacity factor in the United Kingdom is around 10%, half of what it is in Andalucia. So install the solar panel in Spain and transport the electricity.

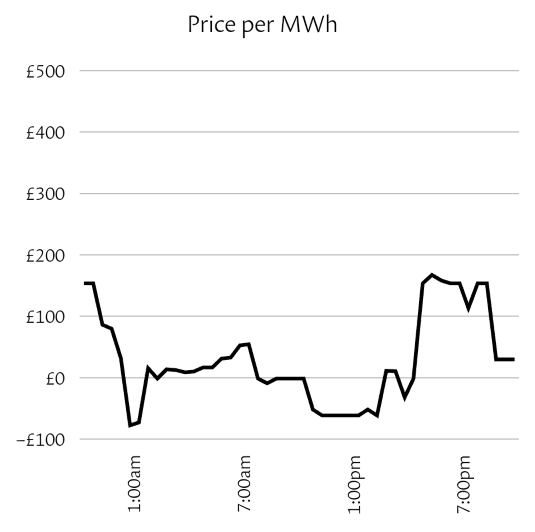

For the discussion on storage, I will start with this graphic which shows what happened to the electricity prices in the UK recently when there was a reasonably warm sunny, windy day:

Source – National Grid: Live (iamkate.com)

The price of electricity was essentially 0 for a period of 14-15 hours. If I look at the forecast for generation capacity, this is where the UK electricity market is heading. Which means there will be a strong incentive to store this electricity somewhere because: firstly, it would otherwise be wasted; secondly, it can be resold at a profit when the market needs it at another time in the day/year. When the market offers these opportunities, someone will find a solution. And given there is already hydrogen on the horizon, I believe this type of market structure is what will see hydrogen take off as a major seasonal store of energy. It can be stored for a long period of time unlike batteries and can be burnt in conventional turbines with gas meaning we have more than one way to balance seasonal shortfalls, i.e. either burn hydrogen or burn gas.

Devi fare login per commentare

Accedi